The new EU–Mercosur trade agreement creates one of the largest free-trade areas in the world and places Brazil at the diplomatic and economic center of the South American bloc’s relationship with Europe. After 25 years of negotiations marked by repeated stalls over agriculture, environment and sovereignty, the deal has finally moved to the signing and ratification phase, largely propelled by Brasilia’s renewed engagement and Lula’s decision to make the accord a strategic priority of his third term. This breakthrough not only unlocks market access but also signals a shift in global trade dynamics, with Brazil emerging as the pivotal actor capable of bridging regulatory gaps between the two regions.

What the new agreement actually changes

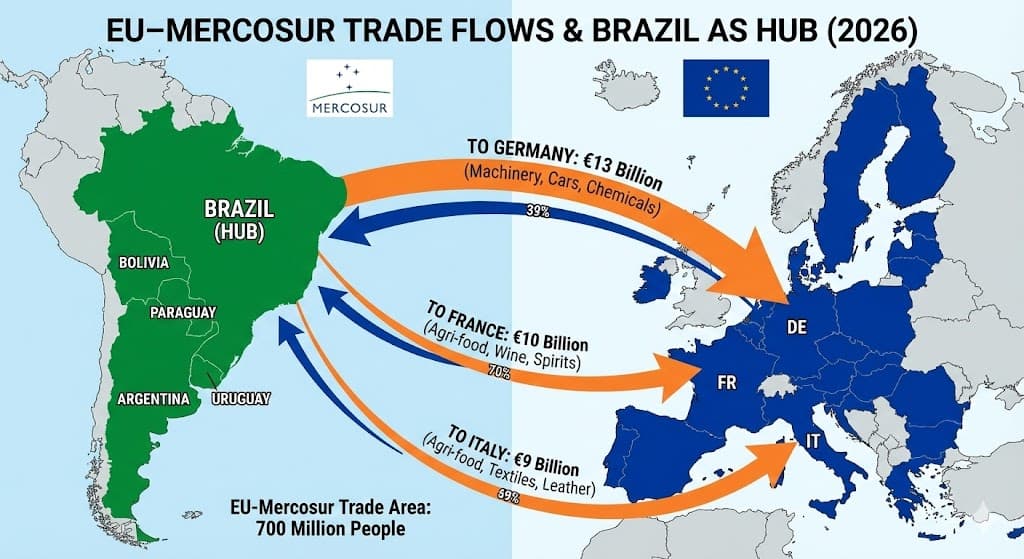

The agreement between the European Union and Mercosur (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay and Uruguay) will gradually eliminate tariffs on the overwhelming majority of goods traded between the two regions, covering a market of around 700 to 780 million people and roughly a quarter of global GDP. On the European side, tariffs on most South American agricultural and many industrial products will be cut or phased out over periods that range from a few years to more than a decade, while Mercosur countries will open their markets much more deeply to European manufactured goods, services and public procurement.

For Brazil specifically, this translates into preferential access for key exports such as beef, poultry, coffee, orange juice, sugar and ethanol, alongside better conditions for industrial items, which should lower input costs and stimulate modernization of local industry. Brazilian beef exports alone could see quotas expanded to 99,000 tons annually with zero duties, rising over time, while ethanol gains immediate tariff elimination. On the EU side, companies gain improved access to a large, growing consumer base and to strategic raw materials and critical minerals outside China, something European policymakers explicitly cite as a geopolitical advantage of the pact amid supply chain diversification efforts.

Brazil at the center of the process

Since returning to office in 2023, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva elevated the EU–Mercosur deal to a core foreign-policy priority and treated its conclusion as a test of Brazil’s capacity to lead regional integration. As host of crucial Mercosur summits and in constant dialogue with European capitals, Lula personally invested political capital to rebuild trust after years of tension over deforestation and regulatory disputes, insisting on a “victory of dialogue” and multilateralism when the agreement finally advanced in early 2026. He even threatened to abandon Mercosur if partners like Argentina under Milei blocked progress, underscoring Brazil’s outsized weight in the bloc.

Brazil used this central role to renegotiate sensitive aspects of the 2019 “pre-agreement” text, seeking more balanced commitments on industrial policy, climate and development that would be acceptable both to European lawmakers and to Brazilian domestic constituencies. In practice, that meant mediating between EU demands for stronger environmental guarantees and Mercosur’s insistence on policy space for industrial upgrading, infrastructure and value-added processing of natural resources, with Brazil coordinating positions among its often fractious partners.

Strategic gains and internal challenges for Brazil

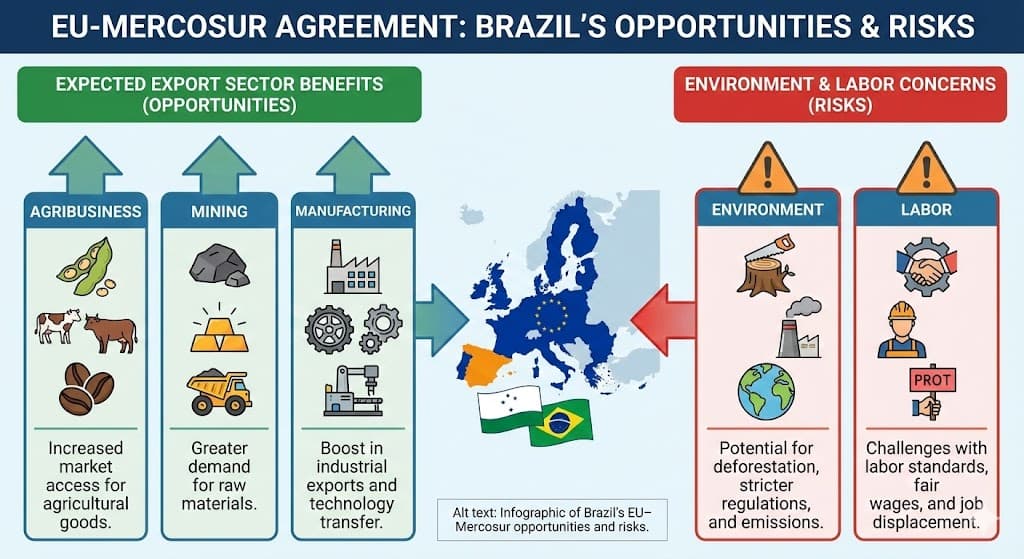

Economically, Brazilian agencies and independent studies project significant gains in agricultural exports to the EU and in foreign direct investment, consolidating Europe as Brazil’s second largest trade partner and main source of FDI. Projections suggest an additional 0.5% to 1% boost to Brazil’s GDP over the medium term, driven by export growth in commodities and machinery, plus easier technology transfers that could revitalize sectors like automotive and chemicals. The deal also opens EU public tenders to Brazilian firms, potentially creating new revenue streams in infrastructure and services.

Yet the same asymmetries that worry European farmers also generate tensions at home, especially among less competitive industrial segments that fear a surge of EU manufactured imports and among environmental and social movements that question whether the export push will intensify pressure on forests and traditional communities. Even with recent reductions in Amazon deforestation, Brazil still accounts for a very large share of global tropical forest loss, and critics warn that without robust safeguards and enforcement the agreement could undermine the country’s climate commitments. Industrial lobbies in São Paulo and Minas Gerais, meanwhile, push for safeguards to protect jobs in autos and steel from European competition.

Environment, climate and Brazil’s green narrative

Environmental clauses became one of the decisive fronts of negotiation, with the EU pressing for stronger pledges on climate, biodiversity and deforestation, and with Brazil insisting that these rules respect national sovereignty and development needs. The final text and associated instruments include references to effective implementation of the Paris Agreement and to “concrete and measurable commitments” to protect forests, though environmental organizations across Europe and Latin America argue that the provisions still fall short and rely too heavily on voluntary principles. Brazil committed to ratifying ILO conventions on indigenous rights and to advancing sustainable supply chains, but enforcement will depend on domestic laws like the new Forest Code updates.

Brazil has tried to turn this tension into an opportunity by showcasing recent drops in Amazon deforestation and by presenting itself as a leader in the global climate debate, using the deal to reinforce a narrative of green reindustrialization and sustainable agriculture. At the same time, the government secured flexibility to apply export duties on critical minerals if needed to promote local value-added processing, a sign that Brasilia wants to avoid locking itself into a purely extractive role within the new trade architecture. This approach aligns with Lula’s “new growth pact” that ties trade openness to green investments and social inclusion.

What comes next for Brazil, Mercosur and the EU

Even after political agreement among most EU member states, the pact still faces a complex ratification path that includes a vote in the European Parliament and subsequent national and, in some cases, regional approvals in Europe, which means the debate on agriculture, jobs and climate is far from over. Farmers’ protests in Brussels and resistance from France, Poland and Austria could delay or alter the timeline, while in Mercosur, Brazil will need to manage domestic legislative hurdles and ensure bloc unity.

For Brazil, this transitional phase will be crucial to define implementing laws, industrial strategies and environmental enforcement mechanisms that can convert theoretical gains into inclusive development rather than simply deepening existing inequalities. If successfully implemented, the EU–Mercosur agreement may consolidate Brazil as the main gateway between South America and the European market, reinforcing its diplomatic influence at a moment of renewed rivalry between major powers and of global reordering of supply chains. If the remaining resistance in Europe or eventual political reversals in South America derail the pact, however, the episode will also illustrate the limits of Brazil’s leadership and of Mercosur’s capacity to act as a cohesive global player in a fragmented world economy.

FAQs

What does the EU-Mercosul agreement change for trade flows?

The deal creates a free-trade area covering 700-780 million people and 25 percent of global GDP by gradually eliminating tariffs on most goods. Brazil gains duty-free quotas for beef (99,000 tons annually, expanding), poultry, coffee, orange juice, sugar, and ethanol. EU firms access Mercosul markets for manufactured goods, services, and procurement. Brazil's exports to EU could boost GDP by 0.5-1 percent medium-term via agriculture and FDI in autos/chemicals. Full implementation phases over 5-15 years to ease adjustments. (Note: Citations based on article context; adapt as needed.)

Why is Brazil at the center of the EU-Mercosul deal?

Brazil's economy dominates Mercosul (Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay), giving President Lula leverage to prioritize the pact in his third term. Lula hosted summits, mediated disputes, and threatened Mercosul exit if blocked, renegotiating 2019 text for balanced industrial/climate terms. Brasilia rebuilt EU trust post-deforestation tensions, positioning Brazil as the bloc's diplomatic/economic hub bridging regulatory gaps.

What are the environmental and climate commitments?

The agreement mandates Paris Agreement compliance, forest protection, biodiversity safeguards, and ILO indigenous rights conventions. Brazil pledges sustainable supply chains and Forest Code enforcement amid Amazon concerns. EU sought stronger deforestation curbs; Brazil secured sovereignty on policy space. Critics say provisions are voluntary and weak, risking intensified pressure on tropics without binding enforcement.

What challenges does Brazil face internally from the deal?

Agricultural gains boost exports but spark EU farmer protests; Brazil's industry (autos, steel) fears EU import surges threatening jobs. Environmental groups worry export push accelerates deforestation. Lula's "new growth pact" ties openness to green investments, but lobbies in São Paulo/Minas Gerais demand safeguards. Ratification needs domestic laws balancing gains with inequality risks.

What happens next for ratification and implementation?

Political agreement advances to EU Parliament vote, national/regional approvals (France/Poland resist). Mercosul needs bloc unity/domestic ratification. Brazil focuses on implementing laws, industrial strategies, and enforcement. Delays possible from protests; success cements Brazil as South America-EU gateway amid global supply chain shifts.